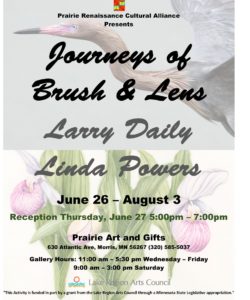

We are excited to have a shared exhibit of our artwork at the PRCA in Morris, Minnesota, June 26 to August 3, 2019 . . . photography by Larry and botanical watercolors by Linda . . .

Travel Posts

Always Take Good Advice…

Always Take Good Advice, Even if it’s Your Own

A piece of advice I always give travelers visiting ‘nature’ areas is: ‘Wear closed shoes when hiking in the jungle’. Trails are often uneven, strewn with leaf litter and sticks, biting creepy-crawlies can get into sandals, trails can be muddy, slippery, and even potentially dangerous, and sturdy hiking boots or shoes are an important tool in securing ‘uneventful’ experiences in the thick of nature.

On a recent trip to the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica, I didn’t heed my own advice, and had to relearn the lesson.

Billed as one of the most biodiverse areas on earth, the Osa covers an area of about 700 square miles, and contains about 2.5% of the world’s biodiversity, while it covers less than a thousandth of a percent of the world’s surface area. It is largely dense jungle (rain forest), mangroves and wetlands, marine habitat, and a few small communities of people.

Linda and I were staying in the middle of the Osa, near the village of Dos Brazos, at a rustic lodging called Los Mineros. We were doing a lot of hiking; looking for birds, plants, other animals, and viewing nature in general. We had heard about an unusual kind of hummingbird, the White-tipped Sicklebill, that had been visiting various heliconia plants along a small river that flowed near our lodging. We had hiked up a trail along the river one morning, without success, and the following morning we had eaten breakfast and were planning our day when we spontaneously decided to try again for the Sicklebill. We were just going to take a few-minute walk up the trail for a couple hundred yards or so, and decided not to ‘gear up’ with camera, tripod, hiking boots, etc, but just walk up the trail with only our binoculars.

The trail was quite reasonable to navigate, even in our ‘Keen’ sandals. It ranged from about a foot to two feet wide, was quite covered with leaf litter, which can be a bit slippery at times, with a few small protruding rocks and sticks. There was a densely forested drop-off of about 10-15 feet down to the river on the right, and an equally densely forested hill rising on the left.

We arrived at one of the heliconia stands, and found no Sicklebill, so continued up the trail. In about 40 yards or so, we caught a glimpse of bird-movement between us and the river, so stopped to investigate. To our great delight, we saw a pair of what looked like antbirds, but we weren’t sure what kind. They are not common, are furtive forest dwellers, and move quickly through the understory, so are difficult to see and VERY difficult to photograph (even impossible without my camera). These two were quite cooperative, however, stopping for several seconds at a time on low branches with good sight-lines. As we watched, I was taking in all the physical attributes of the birds — differences between male and female, exposed bright blue skin around the eyes, blue legs, brown on the back and wings, white breast and belly. I began running through the info about antbirds that I had learned from other tropical birding experiences. A quick review of our Costa Rica birding guide book revealed that they were Bi-colored Antbirds. While called antbirds, they do not hunt or eat ants, but rather follow army-ant swarms to scavenge their prey. I recently learned that they even have a kind of symbiotic relationship with the ants: ‘I won’t eat you if you discard some of your catch for me to eat’.

Since I was unable to get a photo, here is one I got from the website of the Cornel Lab of Ornithology, which allows me to use it as long as I credit the photographer.

© Chris Jiménez

Army ants (of which there are about 200 species) live in groups of up to hundreds of thousands of individuals that maraud through the forest, killing and carrying away anything in their paths (mainly other insects and spiders, but even other small animals as well). If it is something too big to carry, they dismember it and carry the pieces. They have no permanent nests or homes, but form bivouacs, big balls of their entire population, where they stay until they need more food.

About the time this all sunk in on me, and I was thinking, ‘where are the army ants?’, I felt a burning sensation on the little toe of my right foot. I looked down, and saw 4 or 5 army ants gathered on my little toe, between the straps of my Keens, and furiously stinging. As insect stings go, army ant stings aren’t the most painful, about like a honeybee sting if you’re not allergic, but once you feel a few going at your toe, you definitely want it to stop as soon as possible. I reached down to try to sweep them away, but they were too far inside my sandal, so I took my sandal off and got rid of them. I noticed a couple more ants on my sandal which I also swept at, but one was a soldier ant, with large mandibles, and he was clamped down on the bungee lace of my sandal. At that point, Linda took my sandal with the intent of removing that soldier ant, but she was beginning to get stung as well (she was in her sandals too). Well, that ant was very firmly stuck on my sandal, and Linda began looking for a stick to try to dislodge it. I should add that at this time, I realized that she was actually incurring some pain and suffering, but was intent on relieving mine, so I really knew I had picked the right life partner.

There were no sticks within her reach, so she began to move up the trail to find one. This swarm of ants was probably about 25 yards or longer along the trail, and as she reached the end of the swarm, she could look in earnest for a way to remove that pesky soldier from my Keen. Of course, that left me hopping on one foot on a slightly uneven, slightly slippery, leaf-littered trail with thousands upon thousands of army ants teeming at my feet. While it’s bad enough to be hiking through an army ant swarm in sandals, it is much worse hiking barefoot. So I began hopping on one foot in hot pursuit of Linda and my other sandal. Every so-often, I would lose my balance, and put my bare foot down on the trail, in part due the uneven trail, in part due to the desire not to slide down the embankment to the river, and in part from my declining ability to balance on one foot at my age.

So I was hopping after Linda, clomping down hard with each hop to get rid of any ants that were attacking my sandal, stepping down occasionally with my bare foot to catch my balance, then getting my bare foot swarmed with a new crop of ants, and kicking my bare foot to try to dislodge them. Imagine that you have affixed some Scotch tape to the pad of your dog’s paw, and you get the idea. I am ambivalent about not having had someone on hand with an iPhone to take a video of the whole thing.

I was finally able to catch up to Linda, who still could not dislodge that soldier ant from my sandal. On a trip to Ecuador, we had a guide demonstrate how army ant soldiers are used by indigenous people to stitch wounds. They grab a soldier by the thorax and abdomen, pull the skin of the cut together, and bring the ant with its mandibles close to the wound. The ant latches on, closing the wound and holding fast, which works kind of like a surgical staple. They then pinch off the body, leaving only the head with its mandibles to suture the gash. As we thought about it, we realized that the soldier would not let go EVER, so in addition to this being a fruitless removal effort, that ant wasn’t going to attack my foot anyway. I put my sandal back on.

At this point, we decided not to spend any more time viewing that beautiful pair of antbirds, nor to seek a glimpse of the Sicklebill, but to beat a hasty retreat back to the lodge (both sandals on, complete with attached soldier army ant), to ‘lick our wounds’. At the lodge we were given some vinegar and calamine lotion, both of which helped with the pain. I also took a fork and wedged a tine between the mandibles of the ant, and with a surprising amount of effort for such a tiny critter, I was able to remove it. My little toe still burned for a few days, but proved to be only a nuisance. The experience did, however, reinforce the lesson that I should take good advice, even if it came from me in the first place. It was kind of a head-slap moment, but I didn’t do any more trail-hikes in sandals. We never saw the White-tipped Sicklebill.

Countries we have visited . . .

Countries:

Australia – Tasmania

Belize

Canada

China

Costa Rica

Ecuador

England

France

Greece

Hong Kong

Holland

India

Italy

Jamaica

Japan

Mexico

Nicaragua

Norway

Panama

Peru

South Africa

Switzerland

Taiwan

Thailand

Caribbean Islands:

Antigua

Bequia

Canouan

Carriacou

Guadelupe

Martinique

Mustique

St. Lucia

Tobago Cays